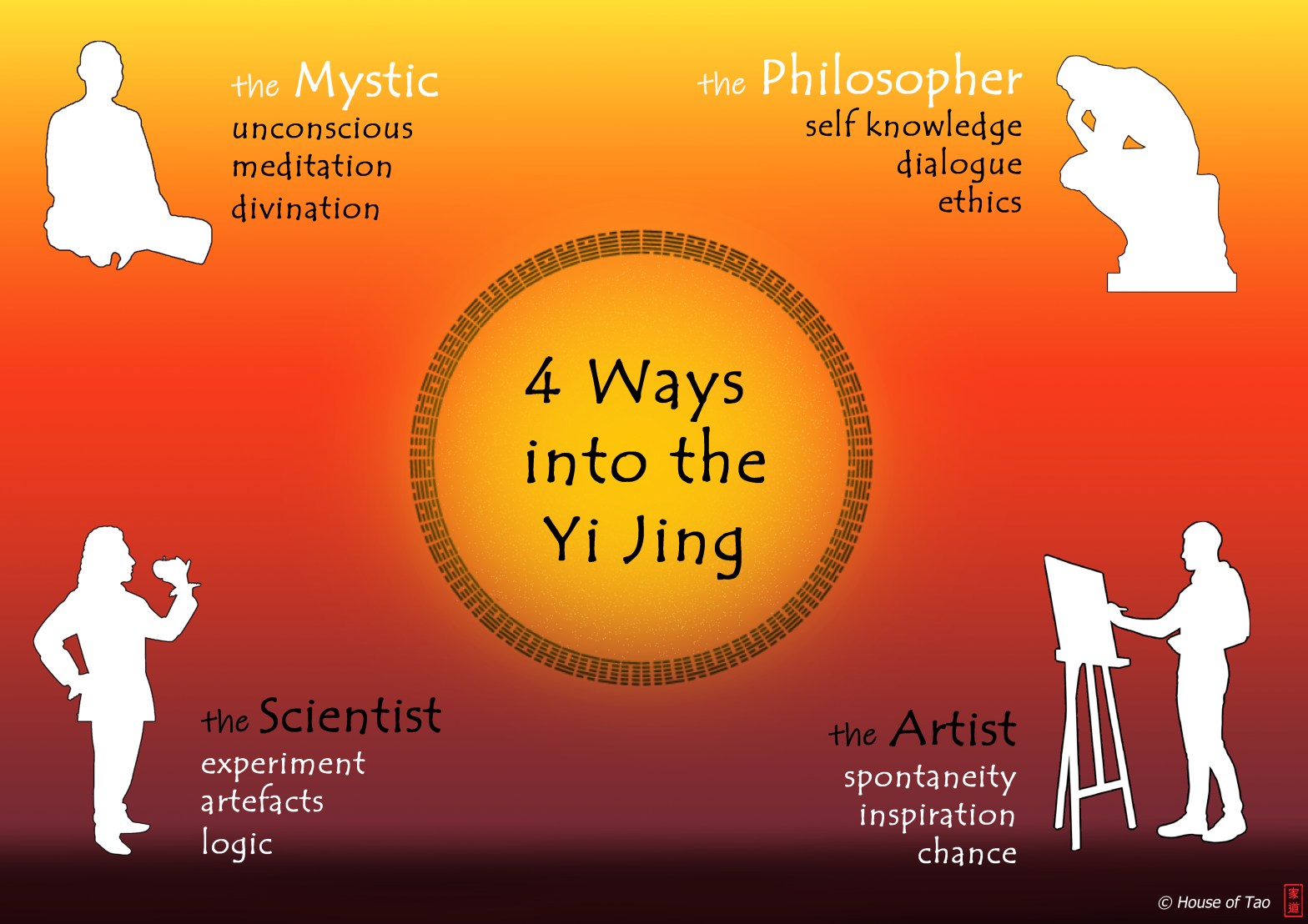

In this second post, we will take a look at some of the possibilities that the role of the Artist can bring when using and studying the Yi Jing. We already talked about the Philosopher where the faculty of “thinking” is obviously central and asked the question: “What is thinking?”

What would be the activity of the Artist and how can we understand this in contrast with the Philosopher? Let us dive in!

Some Keywords:

spontaneity, chance, creativity, fearlessness, beauty, passion

Associated Hexagram:

25 Innocence (The Unexpected)

Beyond Control: Fearlessness

The Yi Jing uses symbols and a highly suggestive poetic form of language that requires us to go beyond intellectual thoughts. These images invite us to dive into a deeper field of meaning which requires a participation of our complete mind. In depth psychology, one would say that the unconscious is also activated, which is the larger part of our psychic energy of which we are just partly aware. This energy also involves the body!

The Yi Jing offers us not just the language to develop these holistic thinking skills, but also the interesting method through divination which allows us to train our mind in letting go and being able to receive an unexpected point of view. This kind of training is very hard to do within our culture where control and planning are the norm. Indeed, “nothing is left to chance” in our society. This obsession of control and the abundance of control systems in our lives are perhaps the very reason we have to deal with so much chaos on a micro and macro level. Even when we are trying to work on our health, whether through food, exercises or meditation, we are often operating from this controling mindset which is counter productive. In the great Eastern philosophy of the Way, Daoism, humans are said to create chaos and disharmony when they obstruct the natural course of things. Wanting complete control through planning instead of mastery from within, is a such a form of obstruction.

In the role of the Artist, we can try to concentrate on finding our point of concentration that leads beyond the obstruction of the controling mind in order to enter the creative mind. Because the Artist has the passionate drive to find something truly novel, he has to open himself completely to the Unexpected. True art expresses something unlimited with limited means, therefore, the Artist must have the courage to jump into the Formless. This formlessness is called Wu in Chinese: the creative void. It is this confrontation with the void that enables the Artist to tap into true creativity.

When divining with the Yi Jing, this jump into the void is unavoidable. Perhaps this process is identical for either role we take up, but what is done with it during and afterwards might be where the difference is situated. How can we experience and express this as an Artist and keep the uncertainty, fearlessness and creativity that comes from Wu?

The Art of the Yi Jing

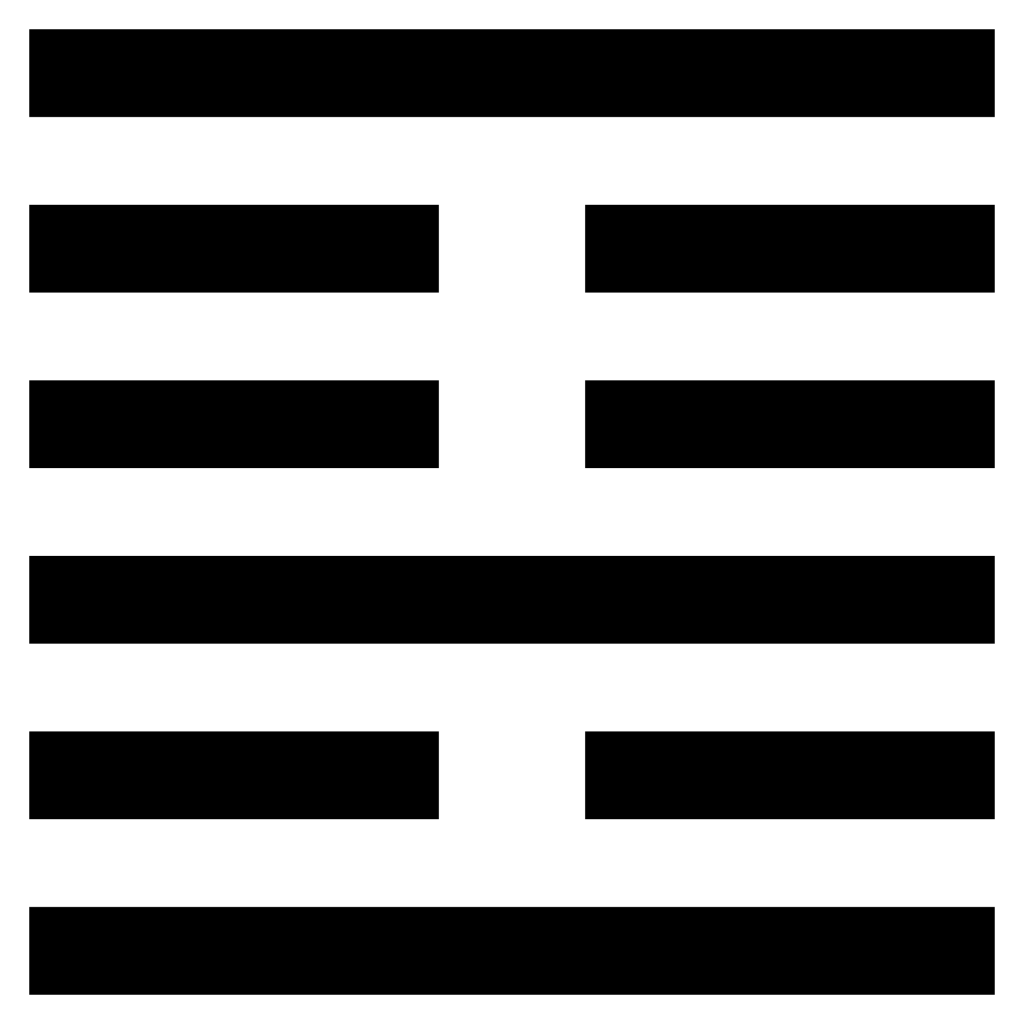

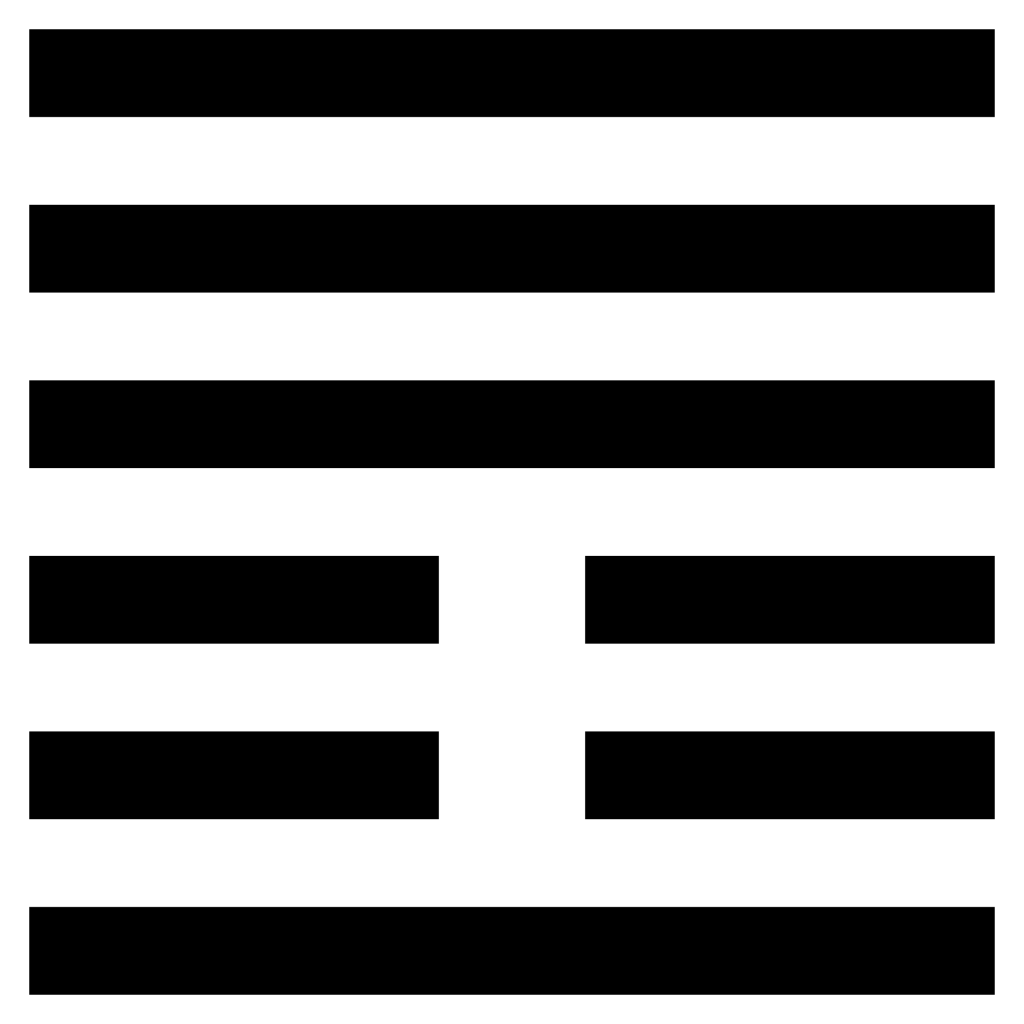

The role of the Artist is perhaps opened up when the art of the Yi Jing itself is recognized and studied. For instance, the language of the Lines in the Yi Jing is a high form of art: it is simple and inspiring at the same time. Without these Lines, the Yi Jing would not be what it is. It is one of the purest forms of expression of the most fundamental principles we can imagine. By expressing the overwhelming complexity of life with the simplicity of open and closed Lines is awe inspiring.

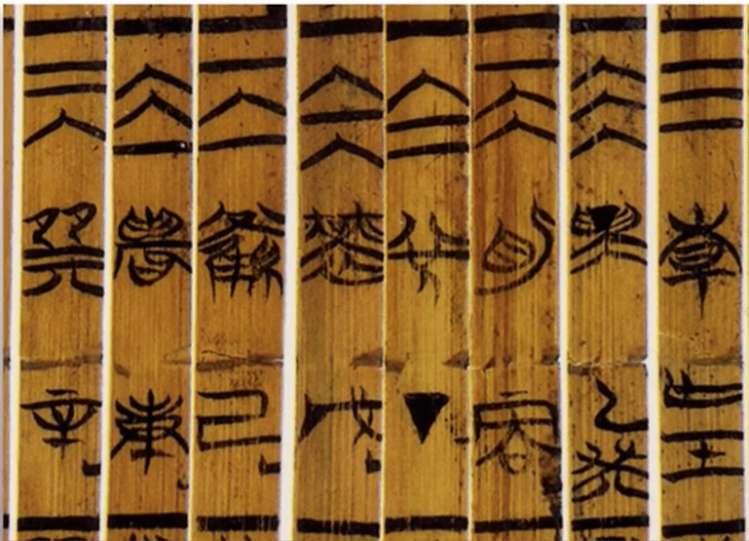

In old Yi Jing scriptures on bamboo strips, we find an alternative way to express the Open or Yin principle: the two short lines form a little roof: Λ. This also beautifully expresses the receptive power, and at the same time it is also able to evoke other important aspects that we learn through studying the meanings of hexagrams which is darkness (below the roof it would be dark), a safe enclosed space (cave, egg, house) and something that can be filled (cauldron, valley, stomach).

The Line art of the Yi Jing is not only helpful to memorize the 64 archetypal chapters of the cosmos, it gives us an aesthetical meaning. When we draw the lines that make up our answer, the combination of open and closed lines is already conveying a message to us just by looking at them. Therefore, the Artist can visually and spontaneously read the Lines without thinking about a fixed knowledge (“this is trigram X”). An important part of the recorded knowledge of the Yi Jing is derived from the aesthetical message of the Lines and their interplay which can give an unexpected message as well.

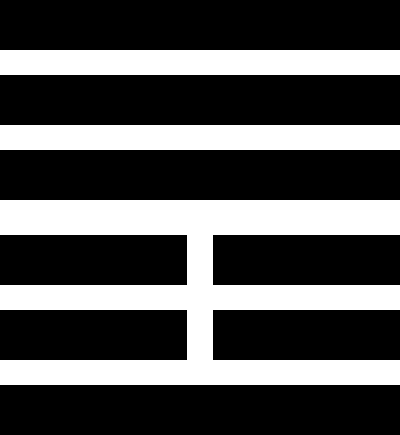

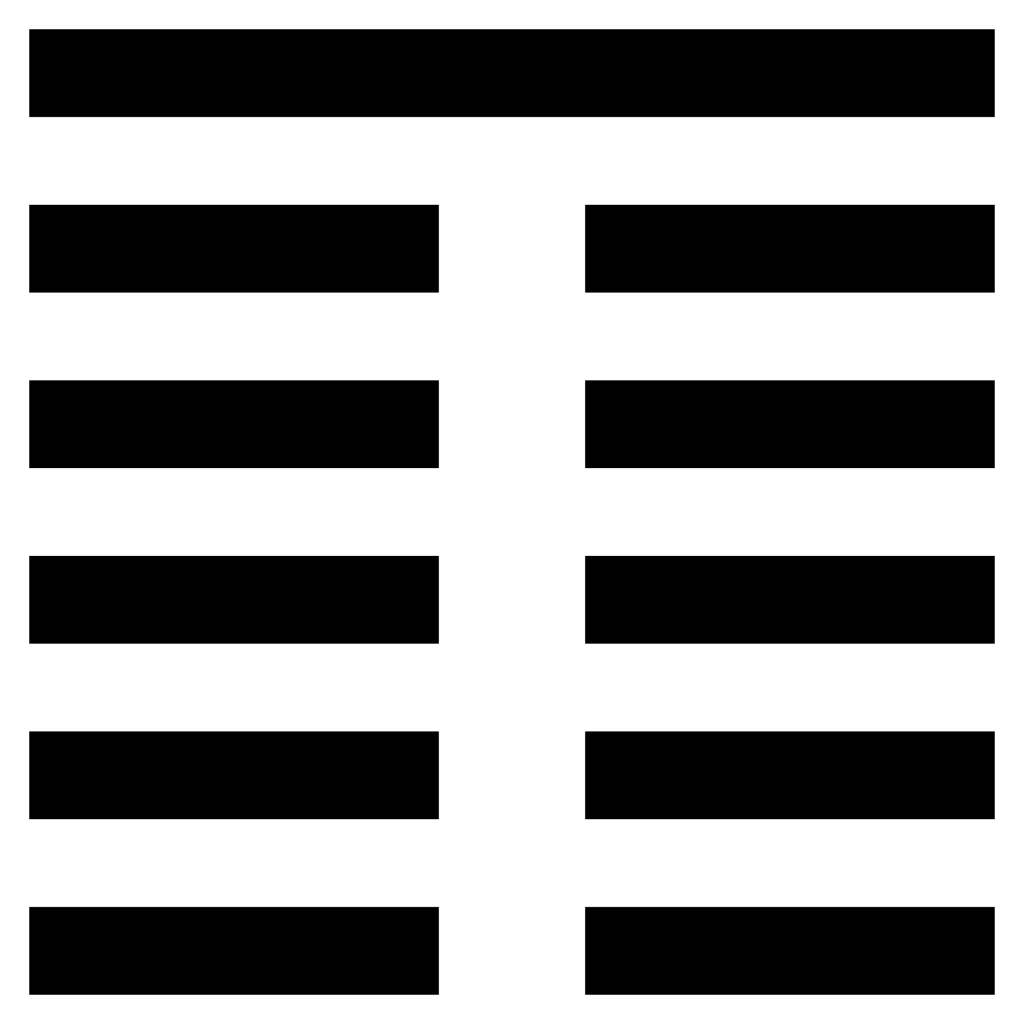

Compare hexagram 23: Splitting Apart with hexagram 20: Watching. I think the lines are clearly telling which one is which.

Splitting Apart gives us an uneasy feeling: all the open lines seem to make the last line “fall”. The last line has no support and is waiting to be split apart as well. In Watching (or Contemplation), the lines could represent a high tower from where we can have a good overview of the landscape of our life. The two solid lines have gone beyond the lower stages of perception. There is no splitting or falling sensation: the two strong lines have an open view aided by the four open lines that suggest an open landscape where nothing is hidden.

Apart from its line art, the language it is written in is also very artistic in its scope: the symbolic imagery and meanings it can convey reminds at once of dreams and poetry. New translations keep appearing that try to “capture” the essence of its language.

Drawing Lines

When writing the answer down, this also offers a chance to express art. By using a calligraphic brush and ink, one can give a serene and truthful expression of the answer to an important question. Instead of writing the answer down only as a way to keep record, it becomes part of the meditative expression of the moment. Drawing either Yin or Yang lines, we can use this moment to connect with the meaning of these symbols and how they follow up on each other.

It need not stop with the open and closed lines. For those who are interested in the Chinese characters, the art of calligraphy will be adding a deeper component to the experience of the philosophy.

Creating Yi Jing Art

Understanding the wisdom of the Yi Jing can take many forms: developing different attitudes, better adapting to situations or change them more easily, making better decisions, and so on. One of these forms of understanding is to create inspiring forms of Art. The Yi Jing has directly inspired a lot of artists or creative people. There are influences in visual art, music, books and so on. Indeed, Chinese tradition has it that the Yi Jing is seen as “the source” of Chinese culture, including the invention of the esthetical dimension of architecture, gardening and so on.

In Chinese paintings, an important principle is that the image must not be identical to what it portrays (just a copy), nor should it be too different (a lie). In order for it to be “art”, it must find that middle way, the sweet spot between two extremes. This naturally leads to a form of art that encourages a certain simplicity of lines. Furthermore, true works of art are produced on rice paper because it allows for the ink to “move” spontaneously as it starts spreading on the thin paper as soon as the pencil has been lifted up. This gives the impression of motion, another important aspect of Chinese art. Life is ever changing and so a painting should not appear to be completely static either.

The Chinese painting above exemplifies this art: the branches of the willow are not just thin, they show flexibility and are dynamic. Quiet movement is insinuated everywhere: the rimpling water of the lake, the strolling man, the waving branches, the bird who flies away. Another aspect is that the inner and outer world are connected: the landscape has a dreamy quality of pensiveness and quietness, reflecting the mood of the man. There is no hard line between the mind of the human and the mind of nature. In the Yi Jing, every situation is able to reflect an inner and outer situation. The upper trigram is often seen as the “outer” trigram and the one below as the “inner”.

The poetic colophon added to the painting conveys more of the meaning of the painting. This one, written by emperor Ningzong, reads: “The wildflowers dance when brushed by my sleeves. Reclusive birds make no sound as they shun the presence of people.”

The art of the Yi Jing is at once a force that inspires a vibration of motion, but also something that calls for peaceful and silent appraisal. The creator(s) of the Yi Jing were artists in every sense of the word, and thus, to use the Yi Jing to inspire the artist, to bring spontaneous energy into this mechanical planned world, is only natural and allows us to connect with the deep essence of its creation.

The gua of Art

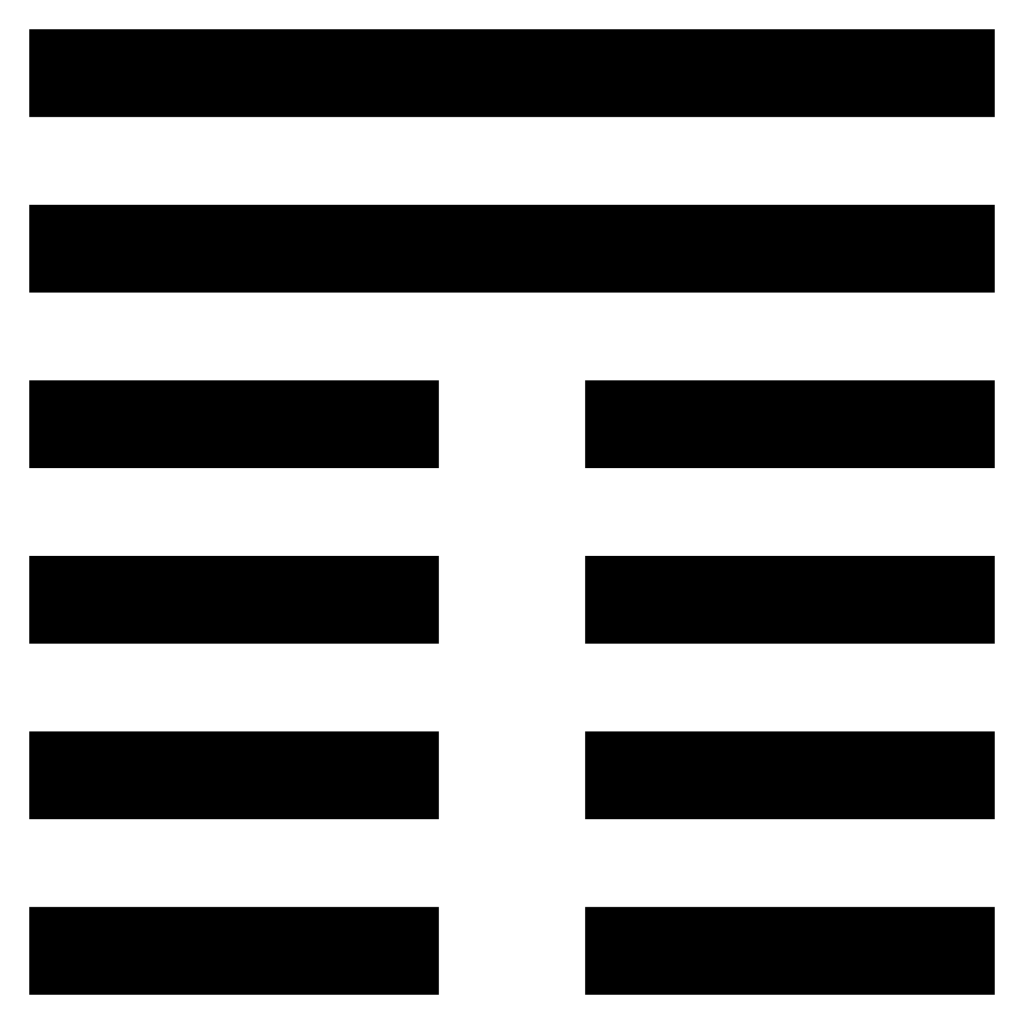

In the Yi we also find that true beauty should be expressed through simplicity. This can be found in hexagram 22: Adornment (or) Grace. The image is that of a secret Fire which erupts from the deep and lights up the beauty of the heavenly Mountain (KEN).

When we create art, we express it with something physical that can be perceived by the senses. Some art has a short time span, such as unrecorded life music, but even then we will have memories about it. Art needs something enduring to exist. And what is more enduring than a Mountain? A Mountain is like a giant sculpture from Nature. It draws Heaven and Earth together in a beautiful tranquility that make us peaceful deep inside. The Mountain illuminated by the Fire (LI) can be seen as the perception of this Art: the fire living in our Mind is needed to bring this artwork to completion. What would art be if there would be no beholder? In the ancient philosophy, humans are not random observers that roam around the world with no purpose: they are the intermediary force between Heaven and Earth in the famous trinity: Tien – Ren – Ti (Heaven – Human – Earth).

One could say that the whole of creation, from potential to expression is a giant artwork in which humans participate by connecting with it: the deeper meaning of Fire (LI) in the Yi is that it “clings”. To behold the beauty of nature is what connects us intimately with it and is essential.

The Artist as Innocent

In the hexagram 25 Innocence, we can understand the importance of the ability to live without planning. The image is of Heaven above Thunder (CHEN): impulses are coming from the spiritual realm. This is what we call intuition: the form of “knowing” where knowledge stops. Every true artist needs a well developed intuition.

INNOCENCE. Supreme success.

Perseverance furthers.

If someone is not as he should be,

He has misfortune,

And it does not further him

To undertake anything.

(Wilhelm transl.)

The hexagram Innocence is about being who you are and to live spontaneously. It is also about dealing with unexpected events, which is exactly what every Yi Jing meditation brings with it. If you are not able to activate the energy of the Artist, it will be very difficult to react spontaneously to the given answer and work with it in a fruitful way. Spontaneity is a core value which is needed in all complete philosophies that seek mastery. Without it, one is stuck in artificial structures, unable to move with the moment. The Book of Changes is here to help us to do that!

In the second line, the advice is given to work on something for the sake of working, without thinking of the results:

2. If one does not count on the harvest while plowing,

Nor on the use of the ground while clearing it,

It furthers one to undertake something.

This advice is clearly applicable to art, because the work put into the art remains more pure and free when the artist is not constantly thinking of how he wants it to be. Every craftsman, musician or artist knows that the wisdom of the body – whether it be through the hands or something else- can only fully act when one is in a relaxed state, allowing the hands to draw or chisel, the voice to sing or the mind to think by itself. It can also be applied to mastering Qi Gong and meditation practices. The student who is constantly thinking about the results he wants to obtain (better health, peace, enlightenment) will be less spontaneous and relaxed. His mind is in a controlling mood and the quality of the work (Gong in Chinese, therefore Qi Gong – “working on your Qi”) will be less. Instead of following the guide of the Qi, the movements will follow the imposed guide of the limited part of the mind.

The philosopher is a role that works its way mostly in the unseen, with as object to arrive at a pure and holistic form of thinking. The artist also connects to the invisible but has the goal to express it into the visible world. The true artists knows that his creativity is partly strange to himself: true art produces unexpected things even for the artist. Yet, he is not a mere puppet of nature but an inspired mediator that uses his own uniqueness to arrive at something new. Trust is needed that from the initial chaos and turbulence, something beautiful can surface. Perhaps it will need a lot of work and polishing, but when true treasures are found, they will require as much effort as they are worth in order for them to shine through.

What are your thoughts on the four roles of the Yi Jing? Tell us in the comments!

In the third part, we will look at the significance of the Scientist when studying the Yi Jing. Be prepared!

Beautiful expression and analysis. As an artist myself I find this article greatly inspiring and enlivening as a way to think about my own practice.

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind comment Andy! Glad to hear that it inspired you.

LikeLike