Since in this way man comes to resemble Heaven and Earth,

he is not in conflict with them. His wisdom embraces all things,

and his Tao brings order into the whole world; therefore he does not err.

He is active everywhere but he does not let himself be carried away.

He rejoices in Heaven and has knowledge of fate, therefore he

is free of care. He is content with his circumstances and genuine in his

kindness, therefore he can practice love.Ta Chuan, Fifth Wing, chapter IV, 3 (Yi Jing, Wilhelm translation)

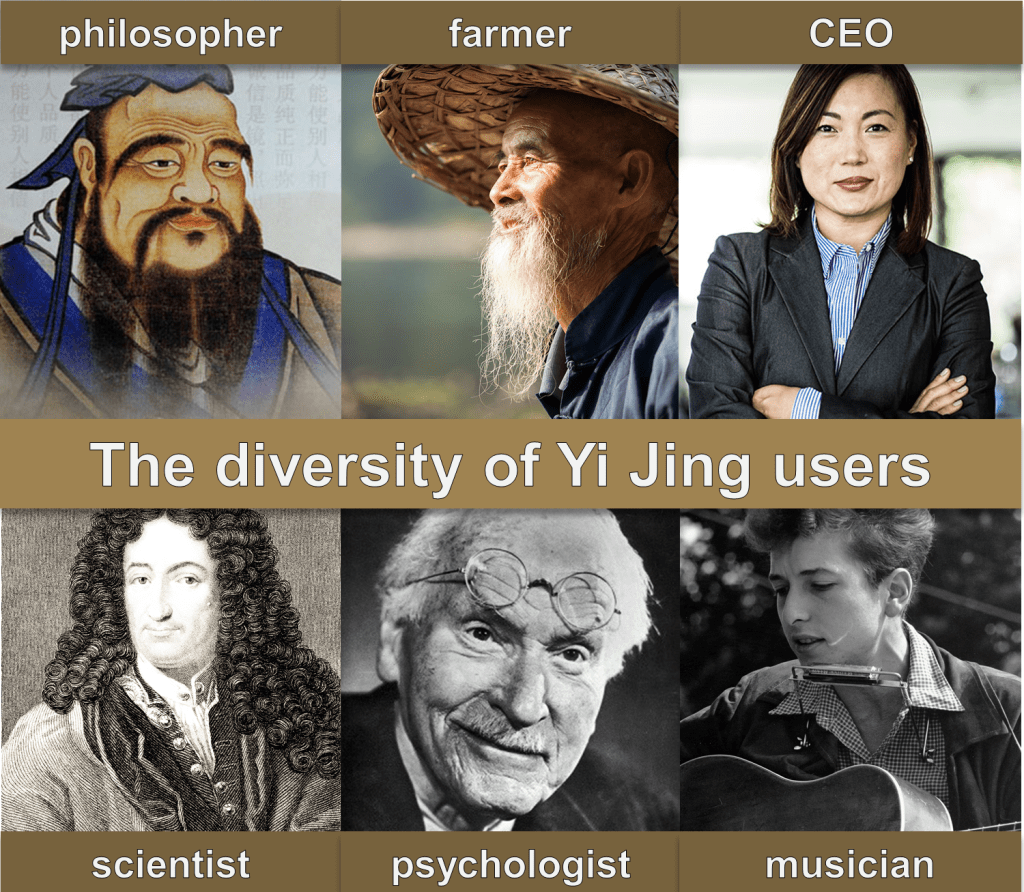

The Book of Changes, Yi Jing in ancient Chinese (other variations are I Ching, Yi King, or simply Yi) is a book that has played the role of oracle, teacher and wise councilor for millions of people. The book has had its reach into religions, statesmanship, business strategies, art, poetry, psychoanalysis and literature and continues to do so. Some well-known people outside China who used or studied the Yi Jing are Leibniz, Hegel, C.G. Jung, Herman Hesse, Jorge Luis Borges, Marten Toonder and Philip K. Dick (“The Man in the High Castle”).

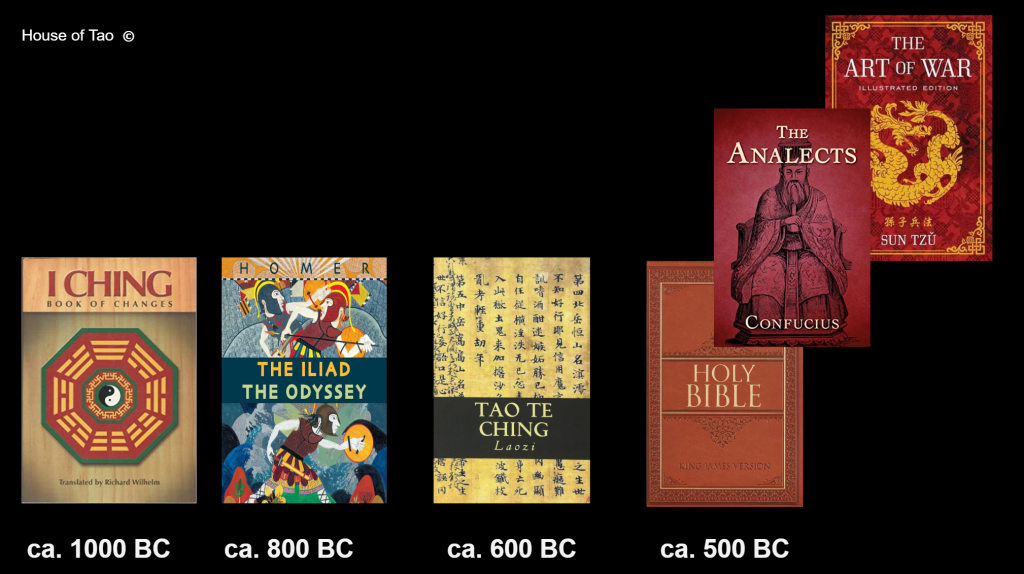

Historically speaking, it is undoubtedly one of the most important scriptures. According to Chinese tradition, it is the foundational work for Chinese culture as a whole. Its ancient philosophy forms the bedrock on which central concepts such as Dao, Yin & Yang, Tai Chi and qi have been founded. Among those who consulted it are no less than the Chinese emperors themselves. It is often called “the bible of the East” and is thought to be at least 3000 years old. Old it may be, all over the world numerous people from all walks of life still consult it like an oracle and/or study it like a book of wisdom in order to grow understanding and wisdom about a situation, or in the broader sense about life itself.

And yet, many people have still not heard from this foundational book. Those that have, often do not know how to read or use it and have their copy of the book collecting dust.

The influence the Yi Jing has exerted on history and people cannot be overestimated and reaches far beyond Eastern Asia. Throughout the times, it has been used to seek council and wisdom by statesmen, sages, leaders, business men and common people. Moreover, since the last century, it has gained a significant following in the Western world, especially through the translated version by Richard Wilhelm and with the help of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung.

The Yi Jing is a peculiar work in that it lays no law, has no religion, no centralized institution behind it, and yet it has spread peacefully throughout the world without a single war. Ever since it has entered the Western world through Jesuits in the 17th century, it has attracted as much intellectuals as it has enchanted intuitive people. We could say that it appeals to both the left and the right brain, the Yin and the Yang, which is not so astonishing as this book is the source from which the famous Yin Yang philosophy sprang forth. Even in our day and age, with all the technology and science that is available to us, a great deal of people (even in high positions of responsibility) prefer to consult the Yi Jing when making big decisions.

Apparently, the Yi Jing is able to cater effortlessly for a vastly diverse public, something it has seemingly always done and continues to do so today. But unlike the bible which has also spawned many different interpretations and churches, the diversity of opinions with regard to the Yi Jing has never lead to any bloodshed or war. So let us keep this tradition of diversity in honor, because true diversity is what our world today lacks the most.

ITS STORY

We all understand that we must read a story to “understand” it. Reading a summary will not do because it cannot be a replacement of actually reading and becoming involved in the story itself. The Yi Jing, however, is not even that kind of a book. It does not offer a clear story to start reading into. It has no beginning and no end, and neither is there a main character. To read the Yi Jing out loud to an outsider, would be like reciting algebraic formulas to a child. It would not only be incomprehensible, it would also be boring. One might say that the Yi Jing is about “the mathematics of life”: it contains the basic formulas on how to live life in harmony with oneself, others and nature.

Yet it is the Book of Changes, Yi meaning “change” (“Jing” is put simple an important book) and that implies that the Yi Jing has not just one or two formulas. Life is always changing, we are always changing, and like a river that flows, nothing ever stands still. As the saying goes, only dead fish go with the flow. The Yi Jing learns one to move in both directions: with and against the flow, back and forth. It is a very good antidote against our modern disease called “progress” where we are convinced that we must always go “forward”, even if that means our own destruction. From the field of changes, the Yi Jing has extracted sixty four basic “formulas of change”: they tell you what kind of change is occurring and what the best approach is in these circumstances. Therefore, the attitude it requires from us is multifaceted: be adaptable when needed, provoke change when the opportunity rises, take small steps at a time, keep still, and so on.

Of course, formulas only become interesting when they are applied to concrete situations. The Yi Jing is no different in this respect. I almost never read the Yi Jing just to read something. It is always in the light of situations and questions that were asked. The Yi Jing requires “input” (a problem, a goal, a situation) to calculate and reflect back an “output”. That is how its words and symbols start generating a meaningful story — that is, to you who gave the input. But the mathematical analogy only takes us so far. In the philosophy of the Yi Jing, the future is not planned, it is a flux of possibilities although not everything is possible. The past too keeps playing a role and can even arise in our future as an obstacle or treasure because for the ancients who wrote the Yi Jing, time is not linear.

Thus, we could say that the story of the Yi Jing is the story of perpetual change and how you — the main character — can surf your way within these changes. This is possible because the principles of change themselves never change. In the philosophy of the Yi Jing, Yi is a principle that encompasses a whole philosophy, similar to Dao. Besides change and the unchanging, Yi is also understood as something which is “easy”.Therefore, to follow the way of change, is to make it easy. Does that not remind you of the Tao Te Ching (Daodejing) by Lao Tzu? It should, because the Yi Jing is much older and laid the foundation for Daoism!

ITS LANGUAGE

The Yi Jing is a surprisingly small book with no more than forty pages in its original language. In the English language, there are a little over 200 translations (research from Bradford Hatcher). Most Yi Jing translations are thick books because the translator(s) have added so many comments. Which is not “bad”, but they are (hopefully helpful) commentaries on the Yi Jing texts. Like an interpretation about a dream is not the dream itself, these commentaries are not the Yi Jing.

The language of the Yi Jing is not only very ancient, it provides little context. Chinese characters are hard to interpret without contextualization. Therefore, translators have many possibilities to explore and this leads to Yi Jing translations that can differ quite a lot. In fact, they can differ so much that they seem to be different books altogether.

Take for instance chapter 15, 謙 Ch’ien. Wilhelm translates this as “Modesty“. Another translation from Karcher (The Total I Ching: Myths for a Change) uses: “Humbling / The Grey One“. What is this “Grey One”? Apparently some kind of a rat that comes to symbolize the quality of humbling in Karcher’s translation. This is based on a certain interpretation of a Chinese character in the text.There is no such hamster in Wilhelm’s translation, just the principle of humility and how this should be understood in different situations.

The first line in Wilhelm reads:

A superior man modest about his modesty

May cross the great water.

Good fortune.

In Karcher it says:

The Grey One biting through. Humbling humbling.

Noble One uses this to step into the Great Stream.

Wise words! The Way is open.

Except for the lack of context in the original text, another reason for these diverse translations is the philosophical inclination of the translator. The translation of Wilhelm is quite old (from the twenties) and has a background in Confucian tradition. Karcher’s version is much more recent (from 2003) and to me it represents a mixture of New Age and academic research (many references to sacrifices).

Although both men have ties to the depth psychology of CG Jung, their Yi Jing translations read very differently. Jung, a friend of Wilhelm, wrote the now famous foreword to his translation and helped introduce the Yi Jing to a wider audience in the West. I highly recommend reading his foreword. Jung takes a pragmatic and anthropological stance and actually shows how he uses the Yi Jing himself. In this case, he personified the book and asked it about the foreword he was going to write, as well as about the new translation by Wilhelm. Both answers of the Yi Jing have proven themselves to be of great value.

Already in more ancient times, it was noted that the Yi Jing acted like a mirror: Confucians found Confucian meanings reflected in it, Daoists Daoist meanings and Buddhists Buddhist meanings. But it would be simplistic to talk about schools only. The Yi Jing has produced thousands of commentaries, all with their personal flavors and colors. Because the Yi Jing is about life itself, to talk or write about it, implies that we will project our own preconceptions about life and reality in it. It is clear then that we will find ourselves more attracted to a version that resonates more with our own life philosophy. But even this can change over time, and a Yi Jing version that did not attract us earlier is seen in a different light.

I personally recommend using different translations simultaneously. They are like different interpretations of the same dream and it can bring the needed depth and width back to your question or situation.

ITS SYMBOLS

The Yi Jing is more than language and translations. It is also visually oriented as each main text is associated with a symbol made of lines. As mentioned before, the Yi Jing orders all change in 64 chapters that contain the “formulas of change” to enlighten us on our situation. Each such chapter comes with a specific line symbol, usually called a hexagram (gua in Chinese). For instance, chapter 15, Modesty comes with following hexagram:

Because the Yi Jing talks through these symbols as well as mytho-poetic language, this has historically lead to two main schools: the School of Images and Numbers that is associated with Taoism and a focus on these so-called hexagrams, and the School of Meanings and Principles that is associated with Confucianism and the study of the texts. I should note here that in the West, we tend to overemphasize the schism between the Confucian en the Taoist tradition. Confucius is regarded by many Taoists as an important enlightened master and his teachings have had ample influence on them as well.

In the West, often the text is given primary attention too, and so we could say that the School of Meanings and Principles is more in vogue. But these line symbols also make up the story of the Yi Jing, they are not just a visual tool to classify the chapters. In some Daoistic traditions, the text is not read at all. Instead, all meaning is extracted from these line symbols. In other words, one does not need to have the Yi Jing as a book in order to “read” it.

YIN & YANG

Now let us look a bit closer at these lines and some of their meanings. A full line represents yang, a broken line stands for yin. It should be noted that the terms “Yin” and “Yang” are younger than these line symbols, but I do not believe that these labels matter that much. It could even be the case that “yin” and “yang” were never written down, because as so much else it was kept in secret and not entrusted to written forms.

strong, masculine, light, action

flexible, feminine, shadow, structure

Here we have a visual and symbolic representation of the two forces that exist in nature according to the philosophy of the Yi Jing. I think the representation is sublime in its simplicity and a powerful way to express the complementarity and difference of Yin and Yang. These lines alone have the potential to speak to our innermost being. The Yi Jing has a short text about each line, sometimes referred to as “the small images” (called yao in Chinese). Depending on their place within a hexagram, a Yin or Yang line is either healthy or disruptive. It is important to note here that interpretations in translations of the Yi Jing can vary about the condition of a line.

HEXAGRAMS

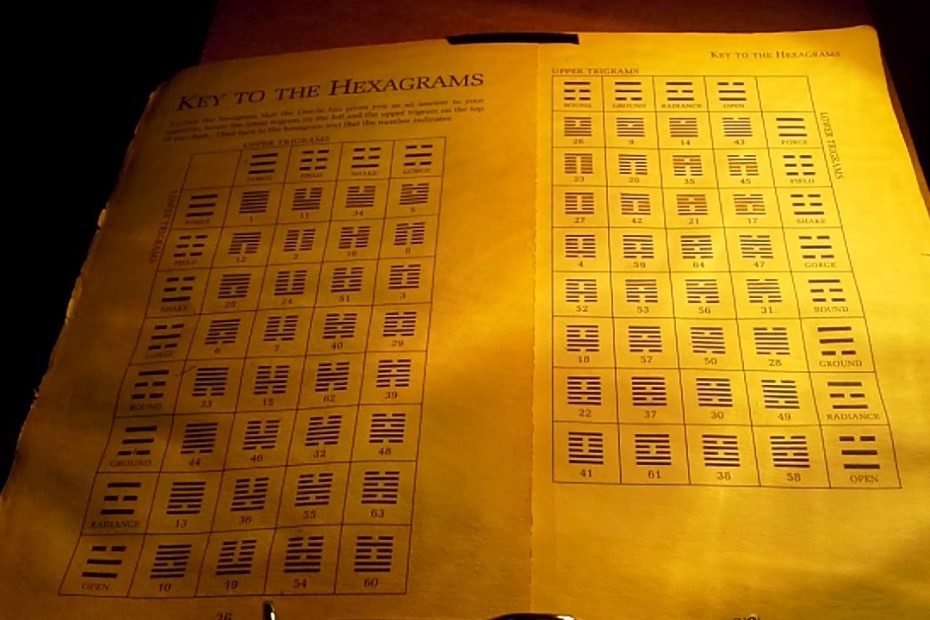

The open and closed lines are gather in groups of 6 lines in the Yi Jing: the aforementioned hexagram. They can be combined in 64 possibilities that represent all the possible variations (2⁶). Traditionally they are ordered in a logical and even mathematical manner according to the so-called Wen sequence. The sequence goes from left to right and starts at the left upper corner with hexagram 1 that consists of only Yang lines: 乾 Qián, with the possible translation “the Creative”. This is followed by hexagram 2 that consists only of Yin lines: 坤 Kūn, “the Receptive”. These two hexagrams occupy a special place: they symbolize the gates of Heaven (Yang) and Earth (Yin) through which all Changes take place.

The Wen sequence derives from King Wen who is the founder of the Zhou dynasty which gave the oldest known name to the Yi Jing, which is Zhou Yi (“The Changes of Zhou”). King Wen is a very important historical and legendary figure in Chinese culture. Tradition attributes the “invention” of the hexagrams with the accompanying short texts (usually called “Judgement”) to him. His name is translated as “The Civilizing” or “the Writer King”. The Yi Jing contains historical references to him and his sons, King Wu and the Duke of Zhou, who waged war against the emperor of the Shang dynasty and overthrew it.

In Chinese tradition, the whole story of the battle against the tyrant of Shang (who had lost touch with the Tao of Heaven) and how the righteous and noble ones overcame it, is projected into the hexagrams of the Yi Jing. It is seen as the exemplary way to overcome a crisis and never to lose faith in the Tao. The Yi Jing version by Alfred Huang offers us this legendary historical view on the Yi Jing.

TRIGRAMS

But according to that same tradition, long before King Wen, the legendary ruler Fu Xi (around 2500 BC) had already realized the basic patterns with which to understand the universe and man’s place in it. These symbols are also made from open and closed lines and are called trigrams (or bagua, literally “eight gua”). There are eight of them and each consists of three lines representing all the possibilities of Yin and Yang (2³). These fundamental principles of reality are represented each by a set of three lines. They can be seen as the building blocks of the Yi Jing and they are extensively used to understand the meaning, energy and imagery of the hexagrams. The trigrams are also used in Feng Shui, some forms of Daoist inner alchemy, as well as in Qi Gong (for example Baduanjin, the 8 Pieces of Brocade).

The symbol I created for House of Tao consists of these eight trigrams (surrounding the sun).

Each trigram is associated with a cluster of meanings on all levels of reality. Examples are body parts, colors, cardinal points, seasons, meditation postures, martial arts movements, human inventions, medicine, emotions, and the list goes on. The eight trigrams can be seen as archetypal forces that are themselves formless. They give form to a multitude of phenomena, both in the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual. Their “name” can thus be translated and interpreted in various ways.

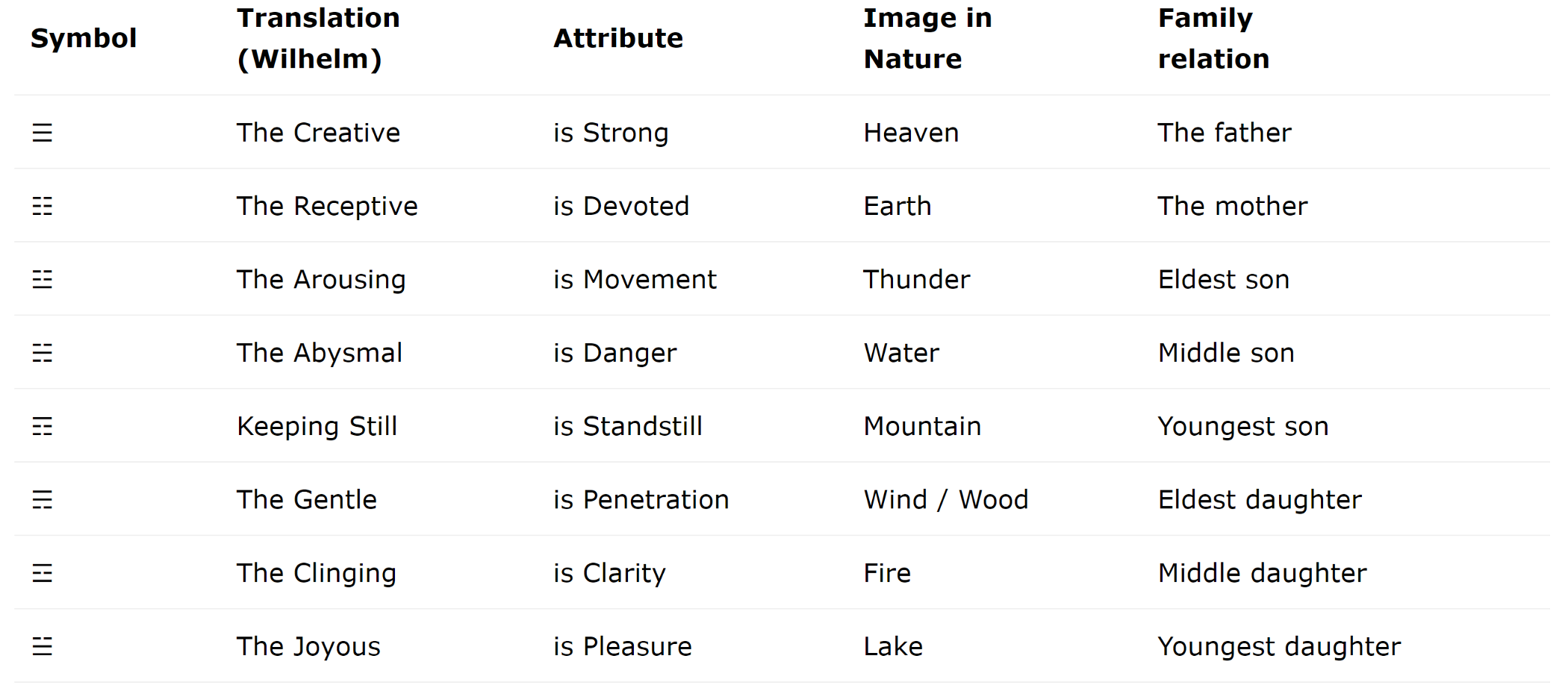

Following table gives the Wilhelm translation and some basic associations of these principles:

The Yi Jing reorders the apparent randomness in life events through these symbolic images and tells us where the handles are to effect change or where to let change happen by itself. Indeed, a good understanding of the Bagua, and how their dynamics interrelate to one another, enables one to grasp the fundamental meaning of the Yi Jing without needing to consult the text. Harmen Mesker, a Yi Jing scholar from the Netherlands, is well-known to teach his students how to use the Yi Jing without the (a) book.

Let us look again at our hexagram 15, “Modesty” in the light of the trigrams:

A mountain that is below the earth, in other words, a hidden mountain in the landscape, evokes the image of a great power that remains modest. The part of the Yi Jing that talks about the images of the trigrams is thought to be of younger date. The Wilhelm translation of the Image of Modesty reads:

The Image

Within the earth, a mountain:

The image of MODESTY.

Thus the superior man reduces that which is too much,

And augments that which is too little.

He weighs things and makes them equal.

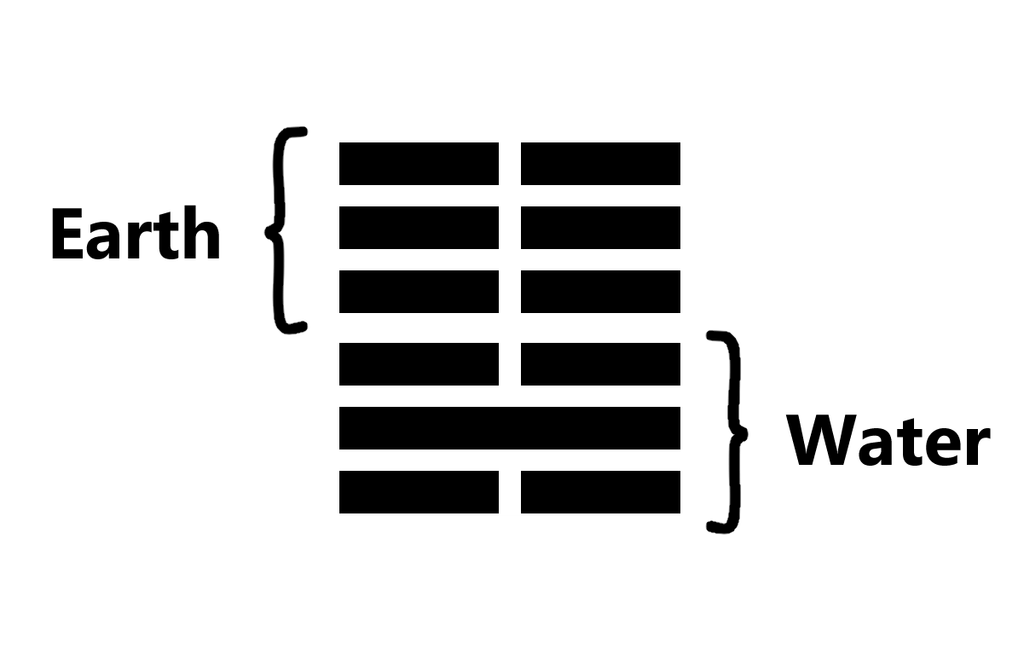

Let us take a look at another hexagram and its trigrams:

The pattern here consists of the upper trigram “Earth” (three open or yin lines) and the lower trigram “Water” (one full yang line surrounded by two yin lines).

This archetypal configuration of Earth and Water, is usually called the Army. Water is associated with danger, it represents the army forces. Earth stands for obedience. In this symbolic image, the army is gathered like water in the ground (Earth).

The text of the hexagram itself is usually called “Judgement”. It is a short text that gives the overall impression and mood of a hexagram. It usually talks about fortune or misfortune.

The Judgement for this hexagram reads as following (Wilhelm translation):

Judgement

The Army. The army needs perseverance and a strong man.

Good fortune without blame.

There is only one yang line in this Hexagram. He is the commander that has to keep all the other yin lines disciplined. He stands at the center of the first trigram (Water) and is in the right place. Therefore, the judgement says “Good fortune”. Wilhelm adds:

An army is a mass that needs organization in order to become a fighting force. Without strict discipline nothing can be accomplished, but this discipline must not be achieved by force. It requires a strong man who captures the hearts of the people and awakens their enthusiasm. In order that he may develop his abilities he needs the complete confidence of his ruler, who must entrust him with full responsibility as long as the war lasts. But war is always a dangerous thing and brings with it destruction and devastation. Therefore it should not be resorted to rashly but, like a poisonous drug, should be used as a last recourse.

That is the general meaning of “The Army”, but we must of course be reminded of the fact that this is just “the formula” without input. The definite meaning always depends on the answer as well. For instance, a couple received this hexagram with regard to their planned wedding. The Yi Jing was right about the circumstances: there was fierce hostility towards the wedding, and a storm of critic and attacks ensued. The couple had a hard time and they needed to organize themselves better to fight for their love. And although the wedding was cancelled, the couple realized that what they really wanted was a marriage in their hearts, not just a formality within a family and society.

As I have already mentioned, the Yi Jing does not favour one general attitude, for example “being peaceful”. When it is time to take forceful action, it will advice to do so. The preference lies not in one limited ideal, but it is firmly grounded in a multidimensional reality. It requires to remain ever flexible in order to adjust oneself to ever changing situations.

BE LIKE WATER ÁND FIRE

The Tao Te Ching is famous for its beautiful philosophical poetry. In general, it promotes an attitude that is often likened to that of Water, hence Yin in nature. The Yi Jing, however, shows us all paths towards self-realization in which Water is but one. The eight forces, the Bagua, are active in and around us and they all need to be lived and accepted. It shows us how Fire and Water, the two primordial forces that represent Heaven and Earth, can be brought to harmony within ourselves. The Wen sequence thus “ends” with hexagrams 63, After Completion and 64, Before Completion, both hexagrams consisting of the trigrams Fire and Water.

Water above Fire

Fire above Water

The 64 Hexagrams of the Yi Jing represent all the archetypal situations we can encounter throughout our life. Some are beneficial and some are not. During beneficial times, it is usually important to remain disciplined because times always change. During hard times, one who can remain patient and keep his calm, is able to store energy and await the right moment to act. Different attitudes or actions are required to either maintain the harmony when we have it, or to create it when we are faced with obstructions and problems. Each problem can also be transmuted into its opposite, namely the solution.

If this article has sparked your interest in the Yi Jing, but has left you with many more question to be researched, then I consider it a success. Hopefully, you will seek out this master work for yourself and explore the possibilities it offers to live a richer life.